The Way of Salt

On Flavour, Memory, and What It Means to Preserve | Season + Brine Like a Chef

Forged in the heart of stars, created through stellar nucleosynthesis to be cast out across the cosmos by dying suns, sodium (the Na in NaCl, salt) has travelled a long way to sit in your kitchen cupboard. Its cosmic resonance gives a yellow emission spectrum so distinctive that astronomers use it to study the atmospheres of distant planets. Jupiter’s moon Io, for example, has a glowing halo of sodium atoms, a ghostly, golden cloud from volcanic salts flung into space.

There are few ingredients more embedded in culture, history, and language as salt. And perhaps surprisingly, we haven’t been sprinkling it on our food for all that long. In contrast, for millennia, it has been quietly lending its metaphorical grit to our ways of describing character, value, and truth, shaping our language and meaning even today, when its use as a preservative or spiritual purity have drifted.

To be the “salt of the earth” is to be pure, essential, without pretension. To be “worth your salt” recalls the ancient Roman salarium, the salt allowance paid to soldiers which was the original salary, and where the meaning of the word comes from. “Take it with a grain of salt” urges scepticism. And to be “salacious” once meant witty or appetising, before the word soured into scandal. In every case, salt is a symbol of flavour, friction, and frankness.

And these phrases are no accident. Salt is friction, and friction is life. In moderation, it reveals truth, in excess, it burns. In speech, as in seasoning, the right amount matters.

In this newsletter,

I invite you to join me on a journey into the incredible world of salt, it’s history, influence, and chemistry. How it sustains us and kills us, why it suspends decay, and a practical lesson on how to use it like a pro in the kitchen for seasoning and brining.

Index

The Significance, Science, & Meaning of Salt

The Body as Salt

Memory Etched in Mineral | Motoi Yamamoto

How to Season & Brine Like a Chef

A Dictionary of Salts

In testament to salt’s preservation abilities,

crystals of halite (rock salt) can trap microscopic bubbles of ancient air, grains of pollen, spores, and even single-celled organisms. Some of these inclusions are millions of years old. In 2000, scientists revived a bacterium from a salt crystal found in a Permian salt bed, a microorganism that had been suspended in mineral stasis for over 250 million years. That’s older than flowering plants and birds, even the breakup of the supercontinent, Pangaea. Imagine going to sleep in a cosy bit of salt only to be awoken by people in lab coats who tell you you’ve overslept a little.

For much of human history, salt has been synonymous with civilisation. Entire economies were shaped by it, trade routes carved across continents, cities founded beside saline springs, and wars waged for access to the white gold. In ancient China, a salt monopoly helped fund the Great Wall. And in West Africa, slabs of salt were traded ounce for ounce with gold.

But its cultural gravity runs deeper and more spiritual than gold. In religious rites across the world, salt is a symbol of incorruptibility and permanence. In the Jewish tradition, salt is offered with bread to sanctify the Sabbath. In Shinto practice, it purifies spaces. Even now, a spilled salt cellar is met with an unconscious flick of the wrist, casting pinches over the left shoulder, a gesture older than most of us realise, and meant to blind the devil that waits behind us all.

In China, salt was not merely a seasoning, it was a foundation of statecraft. As early as the first millennium BCE, the Chinese government recognised that whoever controlled salt, controlled the people. Dynasties rose on its revenues. In the Yan Tie Lun (Discourses on Salt and Iron), a 1st-century BCE record of political debate, officials argued the necessity of a state salt monopoly to fund national defence and infrastructure.

By the Tang dynasty, over half of China’s revenue came from salt. In the Sichuan basin, a technique for salt extraction involved drilling deep brine wells into the ground and transporting gas through bamboo pipes to boil it. In their own way, inventing the earliest example of fracking long before it was ever used for oil and centuries before such technology appeared elsewhere.

Salt wasn’t just a commodity; it was infrastructure, energy, and ideology.

In the kitchen, salt is transformation made tangible. This most democratic of ingredients, affordable and universal, doesn’t just season; it structures flavour. Able to transform the flattest meal, where just a few flakes can make sourness sing, round out sugary sweetness, and awaken umami in waves of depth and richness. It’s not just that salt makes food taste better because we like the taste of salt. It enhances volatile aromatic compounds, suppresses bitterness, and reveals complexity that’s otherwise hidden.

In fermentation, a cornerstone of this newsletter, salt is the gatekeeper. It selects which microbes thrive and which perish, shaping entire microbial ecologies. The brine of sauerkraut, the miso crock, the salt-cured anchovy: are not recipes but collaborations between mineral, microbe, and time. Salt doesn’t preserve by killing, but by curating, it slows down the rot just enough for life to reorganise itself into something delicious.

But salt’s intimacy with the body complicates things.

The Body as Salt

We are saline creatures. Our blood mimics the mineral makeup of the ancient oceans we evolved from. Sodium regulates nerve impulses, muscle contractions, and the fluid balance within our cells. A minimum of 500 mg of sodium per day is required for these essential functions.

Yet excess has consequences. A major 2020 meta-analysis involving over 600,000 participants found that every additional gram of daily sodium increases cardiovascular disease risk by 6%. High sodium intake is firmly linked to elevated blood pressure, which raises the risk of stroke and heart attack. For this reason, health organisations recommend a maximum of 2,000 mg of sodium per day, the equivalent of about 5 grams of salt.

Curiously though, more isn’t always the villain, and less isn’t always the cure. A growing body of meta-research suggests a U-shaped curve, where both very high and very low sodium intakes correlate with higher mortality. Extremely low salt diets may increase insulin resistance, raise LDL cholesterol, and disrupt endocrine function, particularly in those without hypertension. This suggests not a universal villain, but a contextual nutrient: essential in its right measure, risky in excess or absence.

Like fire or wine or grief, salt demands respect. It is a substance of duality; too little, and the body falters; too much, and it stiffens into a chronic burden. The trick, as with fermentation itself, is to let time, need, and awareness lead the way.

In cooking, seasoning food with salt is a very recent culinary venture. Before then, salt was used in the preservation of food, and the salinity of the resulting products were used to imbue its rare qualities in meals indirectly. This is the case with miso, soy sauce, garum, Worcestershire sauce, salted fish, preserved lemons, umeboshi, and so on.

In the Greco-Roman world salt was valued highly, but it wasn’t always sprinkled on food the way we do now. Instead, Romans flavoured food with garum, a fermented fish sauce rich in glutamates and naturally salty. A precursor to Worcestershire sauce of Britain, it was omnipresent, used much like soy sauce is in East Asia.

Early in ancient China, salt was used in soybean fermentations, eventually becoming what we would recognise as soy sauce roughly 2,200 years ago. Direct salting was likely common for preservation, but in terms of flavouring food, people preferred the complexity of fermented salty condiments, which took time, skill, and artisan techniques to make, and offered far greater flavour and depth to a meal than salt could alone.

In medieval Europe, salt became more visible on the table, but even into the Middle Ages, many foods were heavily spiced or seasoned with strong sauces made from anchovies, fermented grains, or herbs in vinegar. Salt was still expensive in many regions, so it wasn’t used as frivolously as it is today.

The more direct use of salt as a table condiment or cooking addition became widespread in Europe around the 16th to 18th centuries, and only more broadly democratised when salt became cheap and widely available, thanks to mining, solar evaporation, and infrastructure like salt roads, taking it from a precious preservative to everyday essential. In France and Britain especially, 17th–18th century cookbooks began to emphasise clarity of taste, simplicity, and the distinct flavours of individual ingredients. Salt, added with restraint, became a way to reveal flavour rather than dominate or obscure it, as garum might, which fell out of fashion after the fall of the Roman Empire (though variants persisted, like colatura di alici in southern Italy).

As culinary tastes shifted from bold, punchy fermented flavours towards delicate, controlled ones, the way we use salt also changed. Paired with greater access to citrus, herbs, spices, and animal fats, cooks had increasingly more tools to create flavour, pushing salt to become one note in a larger composition.

The echos of these older cuisines still sing to the tune of soy sauce, miso, and salted plums in Japan and China. Korea’s doenjang, gochujang, fish sauce, and kimchi. Nam pla, bagoong, and shrimp paste of Southeast Asia. Anchovies, cheeses, and cured meats in Italy, and fermented locust beans (iru), dried fish, or dawadawa in West Africa. Look hard enough, and you’ll find such relics still linger, often offering a window into the flavours that sustained our ancestors the world over.

The Western practice of using salt directly as the main seasoning is relatively modern, rooted in industrial ease and evolving ideas of taste purity.

Consider salt not as a topping, but as an instrument. A sculptor of flavour. On the tongue, it doesn’t just add savour, it balances bitterness, reveals sweetness, and amplifies savoury notes into deep, rounded richness.

A molecular reckoning that begins in the cell wall of a tomato and ends somewhere deep in the folds of the brain. To salt food is to engage in alchemy, not metaphorically, but chemically, biologically, neurologically.

Let’s begin in the pot, where the old myths boil.

You’ve probably heard it before: “Salt your pasta water so it boils faster.” But this is kitchen folklore, charming and false. Salt raises the boiling point of water, just barely. A tablespoon in a pot changes the temperature by half a degree, if that. So no, but the real magic is subtler.

Pasta, like people, absorbs what surrounds it. As it cooks, water penetrates the starch matrix, softening it from within. If the water carries sodium and chloride ions, those minerals seep in too, weaving salt into the very body of the pasta. This is the difference between seasoning and being seasoned. A properly salted noodle needs little adornment, the flavour is baked into its geometry.

And this, curiously, mirrors what salt does to us.

When salt hits the tongue, it begins a chain reaction: sodium ions slip through special channels in our taste receptor cells, setting off electrical signals to the brain’s gustatory cortex. But that’s just the beginning.

It also alters texture. In meat, it denatures proteins, untangling their tight coils and creating room for moisture and flavour to enter. A salt brine doesn’t just sit on the surface, it infiltrates deep into an ingredient over time, carrying with it whatever else is dissolved in the solution: herbs, spices, and aromatics. In vegetables, it draws water out via osmosis, collapsing the cells slightly and leaving them crisp yet pliant. This is why salted cabbage can become soft without cooking, and why a dry brine renders roast chicken so improbably juicy. Salt unlocks the ingredient’s inner landscape.

But most fascinating of all is what happens after salt leaves the tongue. It doesn’t just light up the taste centres of the brain, it activates the insula, the orbitofrontal cortex, even regions linked to memory and emotion. It sparks pleasure not because it’s indulgent, but because it’s vital, an evolutionary wiring speaking to our most primitive urges, to love salt is to stay alive.

There is a poetic irony here: that something as ancient and elemental as salt, a rock from the sea, is what brings life to our food, depth to our flavour, and meaning to our rituals. That a pinch of the right mineral, added at the right time, can make a meal not just palatable, but transcendent. It reveals the structure of a peach’s sweetness, the succulence of a roast, the architecture of an egg. A raw radicchio leaf without salt is all sharp teeth; with a pinch, it softens, and its nuttiness comes forward. A piece of dark chocolate becomes less harsh. A watermelon becomes electric (trust me). It brings food into focus, and it teaches us, again and again, that flavour is not a garnish at the end, but the architecture of understanding, built crystal by crystal.

This is why chefs speak of seasoning not just to taste, but to time. Salt too early, and it draws moisture out; too late, and it remains an exterior dusting. Salt correctly, and it changes the ingredient. Fermenters know this intimately: too much salt suppresses microbial activity; too little, and the brine turns to rot. Salt is neither good nor bad, it is a precise art.

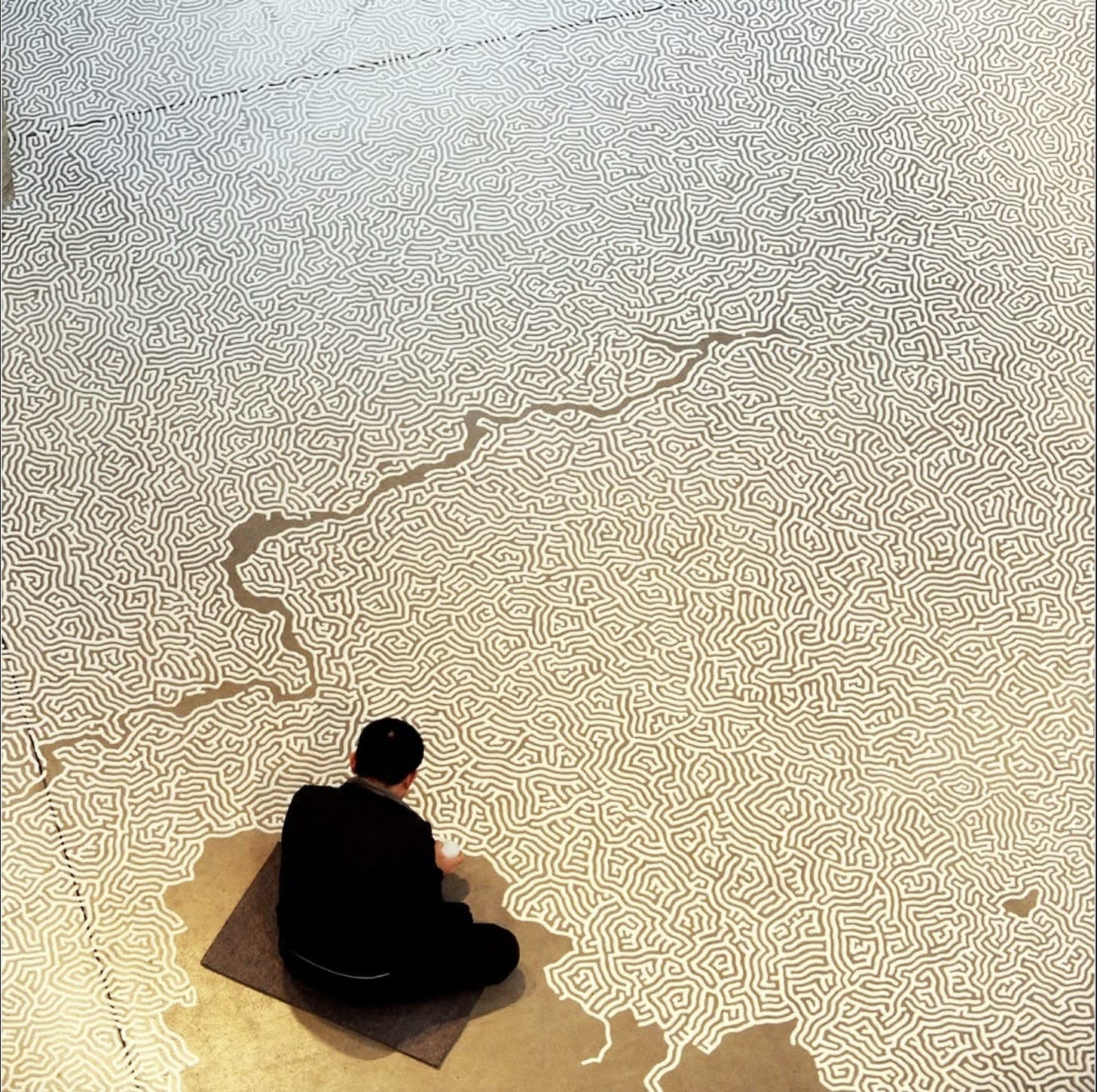

Speaking of which, artists have long understood the polarity and significance of salt. Among these explorations is the work of Japanese artist Motoi Yamamoto, who stands as a singular meditation on salt's profound connection to memory and impermanence.

ARTIST HIGHLIGHT: The Salt Labyrinths of Motoi Yamamoto | Memory Etched in Mineral

In the quietude of a gallery floor, a man kneels, meticulously pouring lines of salt from a small bottle, his movements deliberate. This is Motoi Yamamoto, and the substance he wields is not merely salt, but the crystallised essence of memory, grief, and the ephemeral nature of existence.

Born in Onomichi, Hiroshima Prefecture, in 1966, Yamamoto's journey into salt art began in the wake of personal tragedy. In 1994, he lost his younger sister, Yūko, to brain cancer at the age of 24. Struggling to process his grief, he turned his back on painting and instead, sought a medium that could encapsulate the fragility and transience of life. Salt, with its cultural significance in Japanese funerary rituals as a purifying agent, offered the perfect metaphor. It is both preservative and impermanent, solid yet soluble, much like memory itself.

Yamamoto's installations are vast, intricate labyrinths crafted entirely from salt. Each piece is a temporal monument, painstakingly created over days or weeks, only to be dismantled at the exhibition's end. This act of creation and subsequent dissolution mirrors the human experience of memory, vivid and consuming in the moment, yet inevitably fading with time.

The process is as much a part of the artwork as the finished piece. Yamamoto spends hours in meditative focus, his body enduring the physical toll of kneeling and bending, his mind immersed in recollection. He describes this act as "drawing a labyrinth with salt is like following a trace of my memory. Memories seem to change and vanish as time goes by; however, what I seek is to capture a frozen moment that cannot be attained through pictures or writings."

One of his most poignant works, Return to the Sea, invites viewers to participate in the final act of the installation. At the exhibition's conclusion, attendees gather to dismantle the salt labyrinth, collecting the grains and returning them to the sea. This ritualistic gesture embodies the cyclical nature of life and death, a communal acknowledgment of loss and the impermanence of all things.

Yamamoto's choice of salt extends beyond its symbolic resonance. He is captivated by its physical properties, the way it reflects light, its granular texture, its susceptibility to environmental conditions. In high humidity, the salt absorbs moisture, altering the artwork's appearance, a reminder of the uncontrollable forces that shape our lives and memories.

His installations have graced spaces worldwide, from medieval castles in France to contemporary art museums in Japan. Each setting adds a layer of context, but the core message remains consistent: an invitation to reflect on the delicate balance between remembrance and letting go, which is an experience shared by all.

How to Season with Salt: The Invisible Ingredient

There’s seasoning, and then there’s seasoning, not as an act of adding salt, but of awakening food. To season properly is not to taste salt, but to taste everything more clearly.

Here’s what chefs know, and what home cooks too often overlook:

1. Salt Early (but not always first)

When you salt early in the cooking process, whether you're roasting vegetables, searing meat, or making a sauce, you give the salt time to dissolve, disperse, and deepen. Salt takes time to move. It doesn’t just land; it travels.

For meat and root veg, this means seasoning before heat so that salt penetrates and transforms the interior. For fast-cooking dishes (like scrambled eggs or leafy greens), you may salt later or in stages, layering flavour rather than soaking it.

2. Season in Layers

Good seasoning is additive. A pinch in the onions. A whisper in the sauce. A final scatter just before serving. Each addition builds structure, like scaffolding around the central flavour.

Too much at once and the dish becomes monochrome. Too little, and it collapses. Salt, like light, needs shadow to be seen.

3. Taste Hot

Salt behaves differently when food is warm. Its flavour blooms with temperature, and its perception shifts as fats melt and aromas rise. So always taste just before serving, and let the food tell you if it’s done.

Brining: The Art of Invitation

To brine is not to coat but to invite. It is the gentle persuasion of salt over time, and an infusion, not an imposition.

There are two kinds: wet brining (salt dissolved in water) and dry brining (salt applied directly, often with spices or sugar). Both serve the same goal: to denature proteins, draw moisture inward, and infuse flavour beyond the surface.

Wet Brining Basics

Ratio: About 5–8% salt by weight is ideal for most brines. That’s ~50–80g of salt per litre of water.

Time:

Chicken (whole): 8–12 hours

Pork chops or fish fillets: 30 minutes to 1 hour

Vegetables: 1–2 hours for pickling or overnight for transformation

Extras: Add sugar (for browning), aromatics (peppercorns, bay), or acid (vinegar or citrus) for complexity.

Once removed, pat dry thoroughly. Moisture on the surface = steam, not sear.

Dry Brining Tips

Sprinkle salt evenly over the surface of the ingredient.

Rest uncovered in the fridge:

Poultry: overnight

Steak: 1–3 hours

Mushrooms: 15–20 minutes (to intensify flavour without leaching water)

The salt draws out moisture, which dissolves the salt, then reabsorbs into the flesh. No water bath needed. Just time.

Dry brining is particularly good for crisp skin, intense flavour, and food that needs clarity, not dilution.

How Chefs Use Salt: The Silent Technique

For chefs, salt is not a final act, it’s a constant dialogue. Seasoning is done throughout the cooking process, sometimes, even before it begins. Knowing the type of salt, how to use it, and when, are all vital skills in good cookery.

They use it to:

Balance a dish: cutting sweetness, enhancing acidity, or grounding heat.

Anchor fleeting flavours: salt makes volatile compounds hang on the palate longer.

Reveal texture: a flake of Maldon or Blackthorn on a soft egg, a salted rim against a bitter citrus. Salt contrasts the ingredient's own nature.

They know to:

Salt mushrooms after browning, or risk a soggy pan.

Salt cucumber slices before assembling a salad, letting them weep their excess and gain crunch.

Salt tomato salad only just before serving, or risk a watery bowl.

They understand that:

Acid sharpens, fat carries, but salt lifts.

And in every great kitchen, there is a quiet reverence for finishing salts, not because they are fancy, but because they speak last. They give punctuation to flavour, texture to softness, focus to complexity.

A DICTIONARY OF SALTS

Table Salt

Grain: Very fine, uniformly sized

Flavour: Clean, sharp, often slightly metallic due to additives

Uses: Baking, general seasoning, commercial food production

Notes: Usually contains anti-caking agents and is often iodised. Dissolves quickly and evenly, making it reliable for recipes that demand precision (e.g. baking). However, the flavour is harsher and less nuanced than other salts, and the additional agents make it unsuitable for fermentation and preserving.

Sea Salt

Grain: Medium to coarse flakes or crystals

Flavour: Briny, clean, with trace mineral complexity depending on the source

Uses: Finishing, roasting, salting water, curing

Notes: Harvested from evaporated seawater. Less refined, retaining trace minerals that influence taste. Maldon, Halen Mon, Blackthorn (UK) and Fleur de Sel (France) are famous flaked types; delicate, crunchy, and excellent for finishing.

Kosher Salt

Grain: Large, flaky crystals

Flavour: Clean, not bitter; no additives

Uses: General cooking, dry brining, seasoning meat

Notes: Named for its traditional use in koshering meat. Its coarse texture is ideal for pinching and distributing by hand. It dissolves more slowly than fine salt, making it perfect for cooking but not baking.

Rock Salt (Halite)

Grain: Chunky, irregular crystals

Flavour: Neutral to minerally, depending on origin

Uses: Ice cream making (as freezer salt), curing, salt crusts

Notes: Mined from underground salt deposits. Not usually used directly in food due to impurities but can be used for cooking techniques or homemade salt blocks.

Himalayan Pink Salt

Grain: Crystalline, pale pink to deep rose

Flavour: Mild, slightly mineral

Uses: Finishing, salt blocks, decorative seasoning

Notes: Mined in Pakistan. Contains trace minerals (iron oxide, magnesium). Often overhyped nutritionally, but visually striking and subtly different in flavour.

Fleur de Sel

Grain: Delicate flakes, slightly moist

Flavour: Mild, clean, with a gentle briny sweetness

Uses: Finishing (especially for sweets), salads, fine dining

Notes: Hand-harvested from the surface of salt ponds in France. Expensive, rare, and meant to be savoured. Never cooked into food.

Sel Gris (Grey Salt)

Grain: Coarse, damp crystals

Flavour: Robust, earthy, oceanic

Uses: Roasting, seasoning meat, butter making

Notes: Harvested from the bottom of French salt beds. Its moisture and mineral content make it punchy and textured. Best used where boldness is welcome.

Flake Salt (e.g., Maldon)

Grain: Light, flat flakes that crush easily

Flavour: Mild and clean

Uses: Finishing vegetables, meat, chocolate, bread

Notes: Large surface area means a gentle salt hit with an elegant crunch. Elevates simple food with texture and sparkle. I often use it in fermentation as the mild, clean flavour allows other flavours to shine without being overpowered.

Black Salt (Kala Namak)

Grain: Powdered or crystal

Flavour: Sulphurous, tangy, smoky

Uses: Indian cooking, vegan egg recipes, chutneys

Notes: A volcanic salt rich in iron and sulphur compounds. Its distinctive aroma mimics eggs, used in chaat masala and tofu scrambles.

Smoked Salt

Grain: Varies (often flaky or coarse)

Flavour: Salty with deep wood smoke notes

Uses: Finishing grilled foods, roasted vegetables, tofu, butter

Notes: Cold-smoked over wood (oak, applewood, etc.). Adds complexity to vegetarian dishes and mimics BBQ flavours without a grill.

Pickling Salt

Grain: Fine, similar to table salt but pure

Flavour: Neutral

Uses: Fermenting, preserving, pickling

Notes: No iodine or anti-caking agents, which can cloud brine or affect fermentation. Essential for a clean ferment or clear pickle brine.

Infused Salts (Lemon, Herb, Truffle, etc.)

Grain: Usually flaked or coarse salt base

Flavour: Dependent on added ingredients

Uses: Finishing, seasoning, garnishing

Notes: Excellent for custom blends. Adds visual flair and complexity, think rosemary salt for roast potatoes or citrus salt for grilled fish.

A Final Note

To season with salt is not to dominate, but to edit. Not to overwrite, but to underscore. It is the quietest form of transformation, one that respects the ingredient while making it sing. It is my personal belief that if you can taste salt then you have overdone it. And a word of warning; as is the case with all flavours, you can build a tolerance to the presence of salt in your meals, gradually increasing how much you use over time. Not only is this dangerous for your long-term health, but can lead you towards the habit of overseasoning, potentially ruining the meals you make for others.

In the kitchen and beyond, the most powerful interventions are often the smallest.

Note: For those interested in experiencing Yamamoto's work, his official website https://www.motoi-works.com/en/ offers a comprehensive look at his installations and upcoming exhibitions. Find his Instagram here

This Week’s Music: THE LAMB

I knew, from the moment I started writing this newsletter on a trainride to visit my family, I wanted to share John Tavener’s The Lamb as the music to accompany it. Crystalline in structure and delivery, deceptively simple, yet echoing with depth. Like salt, it begins as something elemental: pure intervals, suspended harmonies, a near-static stillness. But as it unfolds, something remarkable happens. Meaning accumulates and tension breathes beneath the symmetry. The dissonances, subtle as hairline cracks, make the final resolution shimmer with significance. Mirroring our journey with salt from a chemically unremarkable cosmic mineral into salt as experience, transformed into meaning by grief, ritual, preservation, sacrifice, and memory.

In The Lamb, Tavener sets William Blake’s poem, itself a meditation on innocence and divine mystery, but in such a way that it resists emotional excess. It’s not sentimental. It’s a sonic labyrinth, a salt pattern on the floor of a cathedral.

And just like Yamamoto’s work, The Lamb honours what is fragile by not trying to explain it away. It lets mystery be. It lets beauty arrive slowly.

I’d recommend you listen to the full version, this preview cuts short just before the resolution.

As always, thank you so much for joining me on another journey through the delicious details of life. If you’re new here, consider subscribing and make sure not to miss out on future posts. And, if you’re one of those kind people who have already subscribed, please consider sharing this piece.

Until next week,

Sam

Wow Sam this was an incredible read about something I’d always taken for granted, but no longer. Thank you and also thanks for the music and the art. Blown away

Loved this article Sam thank you for bringing all your research and knowledge together. It is a great read and so informative. Please don't despair of substack it needs you 😊