Sat at a table at a book signing event, a lady approached me and started flicking through a copy of my book, The Fermentation Kitchen. To make conversation, I asked if she was interested in fermentation, and she said it was for her friend, who suffered from ulcerative colitis. Making direct eye contact, she said, more as a statement than a question, “I’ve heard fermented foods can help.” I awkwardly stepped straight into my default response of, “I’m afraid I’m not a healthcare professional; I wouldn’t take advice from anyone who isn’t. But my book is more about the flavour, nutrition, and artistry of fermentat—”

She closed the book.

“I’ll do my own research then.” and walked away.

In recent years, a thing I love has been used, misshaped, and abused until it has become something I hardly recognise anymore. Sales teams, corporations, and influencers are all guilty of making outrageous claims around fermentation and its impact on our gut health, sometimes out of wishful thinking, sometimes as a strategy to sell you something. What’s particularly heinous about this is that it is often the vulnerable, chronically ill, or generally people who are striving to live a healthy life who are drawn in by it.

I make a point not to get involved in any kind of drama (you’ll see why at the end of this article), nor do I pay much attention to the world of corporations or social media, but, at the point of writing this, I have the largest account dedicated to fermentation on Instagram. So, I feel a responsibility to share with you, in the most honest and clear way possible, the truth behind what we know regarding fermented foods and gut health. And perhaps more importantly, what we don’t know.

Before we dive in, a caveat. As outlined in my introduction, I am not a doctor. I am not even a chef anymore. I suppose I’m a gardener and author who takes pretty photos. Never take medical advice from anyone, including me, at face value. I got into fermentation over a decade ago, and for me, it’s always been about flavour. Having said that, I do a huge amount of research in my own time on safety, technique, health, and microbiology. Partly because I want to make sure the recipes I share are safe, and partly because I’m hungry to learn. I always do my best to read research publications thoroughly, inspecting them for vagueness and conflicts of interest. If a paper has been peer-reviewed, then who by? Was there a conflict of interest in who funded the research? Was it part of a meta-analysis or an opinion piece?

What I present here is the most up-to-date and honest report I can give on the actual science of fermented foods, gut health, and the gut microbiome. Having tentatively shared a similar piece on my social media, I was relieved to have many doctors, microbiologists, and relevant specialists reach out to me with confirmation of everything I wrote. But if you have reason to believe something I’ve said is wrong, please let me know in the comments and provide sources to the research you’ve read (or anecdotal evidence).

And, if you are someone who suffers from some kind of chronic illness and turned to fermentation as a possible aid, please do not let this newsletter deter you. What I’m about to outline is the difference between what is likely, what is known, and what is pure speculation. If you have tried something and you feel good about it, by all means, continue.

The Gut Microbiome Investigation

The gut microbiome is one of the most researched and hotly debated topics in science today. With varying degrees of success, gut health is being investigated in connection to: inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, acute malnutrition, diabetes, obesity, hepatic encephalopathy (a decline in brain function with severe liver disease), arthritis, skin cancer, living transplants, autoimmune disease, Alzheimer’s, neurodevelopmental disorders, depression, hair loss, bipolar disorder, neurodegenerative disease, and UTIs.

There is growing evidence of the connection between what we feed ourselves, and therefore our microbiomes, and our health, including that of the mind. Most alarming is that of the ultra-processed diet up to 57% of the US population consumes and the severe impact on the gut microbiome and subsequent health issues. But there is little to no conclusive evidence that eating a jar of raw fermented food has a measurable impact on the overall health of the gut microbiome.

To my fermenter’s mind, it makes sense that a microbially rich vessel, be that a jar of fermenting ingredients or your gut microbiome, is an ecosystem of trillions of interconnected organisms. Adding a few drops of vinegar culture into a sauerkraut isn’t going to turn the entire thing into a cabbage vinegar. This is because the competition overpowers it. In the case of sickness, a pathogen that tears through your gut microbiome is so aggressive it can overcome this internal ecosystem and requires the full force of your immune system (and, in some cases, antibiotics) to remove it. This is a theory behind the evolutionary advantage of having an appendix. This small, unassuming organ is home to a vast and diverse number of microbial species that can weather such an infection from days before antibiotics, then slowly repopulate your gut once the immune system has done its job.

To bolster this point, in recent years, gastroenterologists have started treating individuals with chronic bowel-related diseases with FMT (faecal microbiota transplant) from healthy donors. Despite being a very direct way of bypassing the hostile defences of your stomach acid and bile, patients are often still given a course of antibiotics prior to transplant to hammer their native microbiome and lessen the competition against the new ones.

I promise, that will be the only time I talk about poo in this newsletter. My apologies if you were eating.

But before we get into fermentation, let’s introduce you to your gut microbiome.

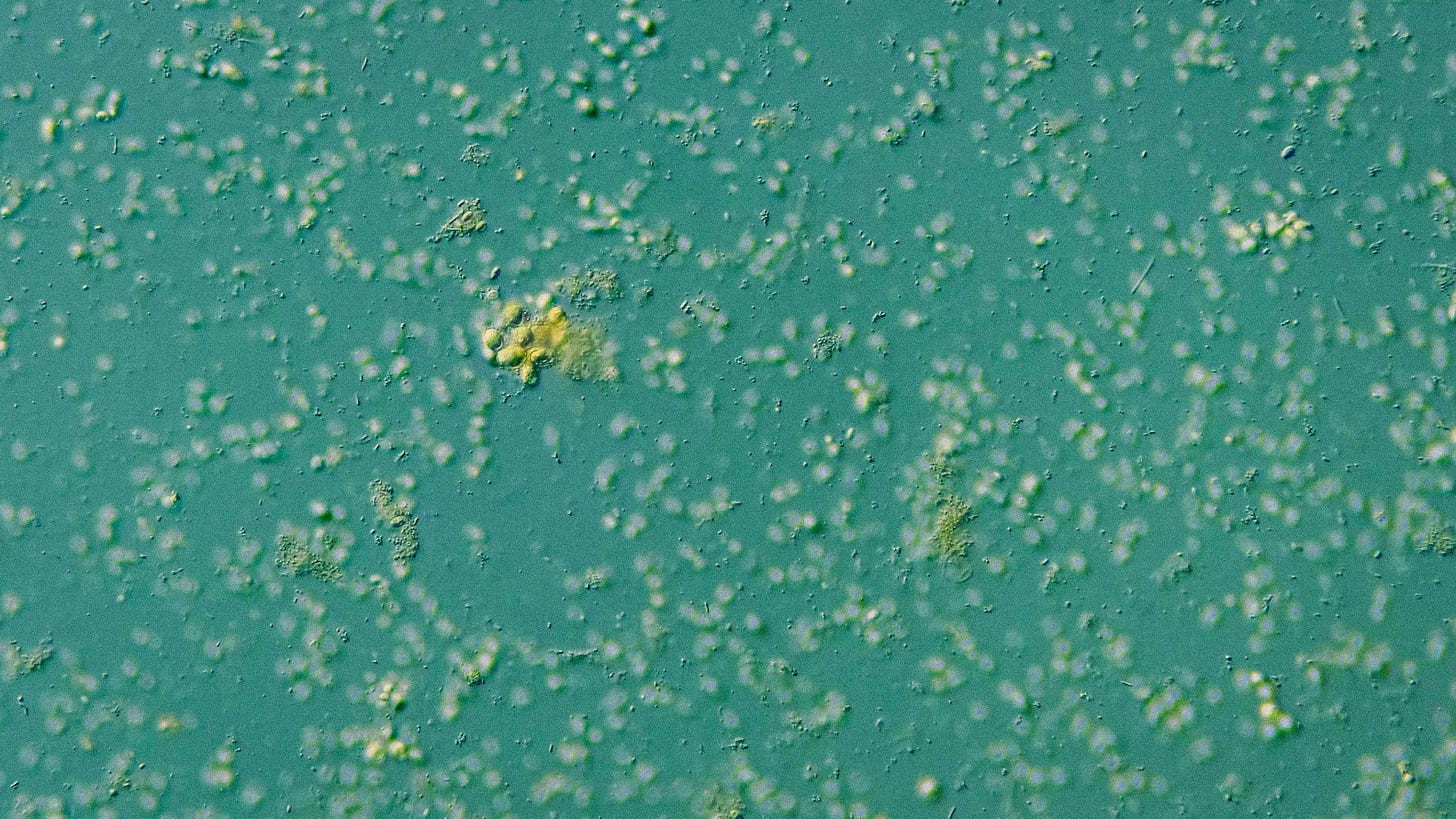

A Journey Through Your Microcosmos

You house, in your gut alone, 1.5 kg of bacteria. If that sounds like a lot, it is. In weight, it equals that of the liver, which is the largest organ in your body. The gut microbiome is made up of 100 trillion bacterial cells, outnumbering the cells that make up you, meaning there is more of you that doesn’t share your genetic code than there is that does. Your gut isn’t the only home you provide for microbes either, with populations of hundreds of billions of bacteria quietly minding their own business in your skin, mouth, stomach, duodenum, and small bowel. There are even huge variations within each biome; for example, the species found on the skin on your feet are different from those on your legs. Your intestine is lined with thousands of villi, tiny finger-like projections that absorb nutrients from the food you digest. Despite being only 0.5-1.6 mm long, there is a difference in microbiome at the tip and base of each villus.

The gut itself is home to predominantly four of the 104 bacterial phyla: Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria. You are also home to a tremendous number of fungi species (206 on average), found to support gut biome structure, metabolic function, and immune priming. Immune priming in particular is very interesting. This is when certain fungal species (e.g., Candida albicans) switch on your immune system against their competition by producing the chemical signatures of their competitors. Your immune system learns to look out for these and quickly targets them when they appear, acting in a similar way to a vaccine. Then there are the archaea, a separate domain of life from bacteria and eukarya, that are estimated to make up just 1.2% of the microbial population of our microbiomes, but they form an important regulatory role nonetheless.

Smaller still, there are viruses, collectively known as your virome. There are 142,000 species of viruses, which aren’t technically a form of life, but they play a vital role in population control. Worldwide, viruses are responsible for wiping out half the bacteria on Earth every 48 hours. Viruses also encourage the act of gene transfer between organisms, splicing in and out genes in bacteria’s genetic memory with influences that protect them from future parasitic infection. This discovery is actually what inspired gene-editing technology.

Thanks to this horizontal gene transfer (as opposed to the genes that are passed down from generation to generation), it is estimated that 8% of the genes you carry are ancient code from other microorganisms, some of which are millions of years old and show signs of previous global pandemics, further blurring the boundary and subsequent definition between what we perceive of ourselves and what we perceive as distinct from ourselves. Where do I stop and the world begin?

The microbiome is an extension of your genome, one you first inherited from your mother and continued to nurture with every action and meal. The wisdom found in the phrase “You are what you eat” couldn’t be more true, and the rise of ultra-processed foods, junk food, high salt intake, high-protein diets, and a lack of diversity and fibre all indicate the degradation of our internal ecosystems and the mass extinction of entire species within our microbiomes. For example, members of the phylum Bacteroidetes consume nitrogen more readily than other microbes, leading to an imbalance in individuals with high meat consumption* (meat contains an average of 64–134g of nitrogen per kilogram, compared to plants with an average of 5–22g per kilogram). Eat more veggies, kids.

* I don’t mean to demonise any one food group and personally take the approach of everything in moderation. After all, well-produced animal products are also highly nutrient-dense.

Lifestyle, air quality, and medical practices have all contributed to the loss of diversity within our gut microbiomes, and perhaps more alarmingly, we also observe mutations occurring. Without understanding and nurturing our gut microbiomes, we could lose more than our health—we could lose our minds.

Our brain is in constant communication with our gut microbiome via a three-way system: through the production of neurotransmitters like serotonin, through the hormones in our endocrine system, and through the immune system. A human hormone like adrenaline can be received as a signal by groups of bacteria in the gut that respond accordingly. In recent decades, entire scientific fields have been established in response to the gut-brain axis, like the psychobiome, which researches the complex relationship between the microorganisms in the gut and how they affect mental health and well-being. This ranges from behavioural responses in illness, such as a lack of appetite, to long-term chronic conditions like depression or bipolar disorder.

It is now speculated that conditions like IBS (irritable bowel syndrome) might stem more from the mind than they do the bowel, implying a potent physical reaction to the kinds of anxieties and stress we experience in day-to-day life.

If our brain is in conversation with our gut microbes, it begs the question: do microbes play a role in human sentience? Could we be experiencing a collective symbiotic consciousness? And what happens to human sentience when entire species disappear?

Believe it or not, that was the nutshell version of where we’re currently at in our research and understanding of the gut microbiome.

What Fermented Foods Actually Do

At the time of writing this, there is no conclusive evidence that eating raw, fermented foods has a measurable positive effect on overall health, despite the number of studies being carried out. Part of the reason for this is the gut microbiome is an exceedingly tricky thing to study. The moment you study an individual’s gut microbiome, you disturb it, introducing foreign microbes and external conditions.

So, anybody claiming with any degree of certainty that eating a particular food will fix everything listed in the previous 2,000-word journey through the microbiome in all its wondrous complexities has commendable optimism (or a sly marketing strategy).

What we do know fermented foods do:

Make nutrients in ingredients more bioavailable for our bodies by subjecting them to ‘pre-digestion’ through fermentation.

Neutralise certain toxins and digestion-inhibiting compounds.

Preserve ingredients.

Fundamentally and chemically alter ingredients.

Unlock an incredible range of flavours, aromas, and textures.

Provide digestion-aiding enzymes that our bodies and microbiomes cannot alone.

Bring people together from all walks of life.

There are studies that indicate eating fermented dairy products like natural yoghurt or kefir could have an effect on gut microbiome structure. The extent of this has not been measured, nor has conclusive evidence been provided.

There has even been a correlation noted between an increased population of certain microbes commonly found in fermented foods and illness. Though there is no evidence which is the cause of the other. Does an increase in population lead to illness? Or does the illness lead to an imbalance of microbes?

Where there is a gap in our knowledge, people will fill it with myths and gods. If fermentation was the holy grail for human health, we’d see populations around the world that consume the most enjoying the greatest benefits, but this isn’t the case. Instead, it’s often those with the least processed food, least industrialised lifestyle, least polluted countries, strongest sense of community, least consumption-driven appetite, and most casually active. Fermentation doesn’t even feature.

Speculations & Profits

There are numerous studies on fermented food and their impact on the gut microbiome and none have provided conclusive evidence of any overall improvement in health. Certain microbes have been linked to certain health conditions, but it still isn’t clear which causes the other. It is often the case that many people live happy, healthy lives whilst carrying the same bacterial species that causes chronic complications in others.

The same is true for foods. Not only do some people suffer from allergies and intolerances to certain foods, but even within the same family, certain individuals get a sugar spike from eating a bowl of rice but not from pasta, and vice versa.

Be highly skeptical of anyone offering you a kefir shot or kombucha as a supplementary cure-all. Whilst there are studies that imply there could be a connection between certain fermented foods and a difference in microbiome structure, we are far from knowing the facts for certain. For most companies it’s simply business as usual, some other way to make money from you, and they’re in a race to get their products out first.

Ancient Wisdom VS Modern Science

When I posted about this subject on social media, the main pushback I received was against modern science. The notion that ‘science rediscovers what ancient wisdom already knows and labels it with a certificate’ made me realise how little faith some have in an evidence-based mode of observation. I understand that things get muddy when it comes to private investment, conflicts of interest, and healthcare with a focus on profit, but these are issues that face each and every sector.

Do we think that a shaman in the woods who offers us a healing cup of tea in return for payment isn’t financially motivated to big-up the effects of his concoction? Before there was even money, there was conflict of interest.

But science is at once bigger and smaller than pharmaceutical companies. At its core, it is an investigation into the workings of the world. Can it be wrong? Of course, anything touched by humans is fallible. But I have as much faith in modern science as I do ancient wisdom, with a healthy degree of scepticism for both. On the one hand, we have the widespread overuse of antibiotics and chemical fertilisers; on the other, thousands of deaths from toxins and food poisoning that some individuals overlook in their fetishisation of historical and localised practices.

For example, in 1988, the year I was born, tempe bongkrek of Java, Indonesia, was banned. The traditional food, which had been made for hundreds of years, was served as a main source of protein in Java due to its inexpensive manufacturing. Tempe bongkrek, made by extracting the meat by-product of coconut milk to form a cake, was fermented with R. oligosporus mould, but prone to poisoning from a bacterium called Burkholderia cocovenenans (formerly Pseudomonas cocovenenans), which is commonly found in plants and soil and taken up by coconuts and corn. This led to the synthesis of bongkrek acid during fermentation, which became a widespread issue during the 1930s when Indonesia went through an economic depression, causing some to attempt making tempe bongkrek themselves without proper training. As a result, poisoning occurred frequently enough that Dutch scientists W. K. Mertens and A. G. van Veen from the Eijkman Institute of Jakarta began researching the food and identified the cause in the early 1930s.

Since 1975, consumption of contaminated tempe bongkrek has caused more than 3,000 recorded cases of bongkrek acid poisoning, with a staggering 60% mortality rate and can kill in as little as an hour. Compare this with botulism poisoning, which has a mortality rate of 5–10% (40–50% if untreated).

I don’t mean to scare you off fermented foods by writing this, nor needlessly fearmonger. My point is that a trust in ‘ancient wisdom’ over modern science can be misplaced. As can a disregard for anything that came prior to modern science. This isn’t about picking a side; it’s about proceeding with sound judgement and consideration.

My Dull But Realistic Advice

So, what would I, an ex-chef, gardener, and definitely NOT medically trained health expert, advise you to do if you want to look after your gut microbiome?

There is no holy grail, and a focus on such things serves only to distract us from the incremental daily choices that gradually make the biggest difference.

Eat lots of plants, lots of variety, and plenty of fibre. When possible, stick with organic whole foods, and make sure to drink plenty of water each day. Aim for 7–9 hours of good quality sleep each night. Enjoy fermented foods too, which are often far more digestible for both you and your beloved microbes, and provide additional enzymes, nutrients, and acids that aid in digestion and health. These include natural yoghurt, kimchi, sauerkraut, miso, kefir, kombucha, and vinegar. Avoid an excess of high-fat and high-protein foods. Heaven knows we’ve been overconsuming protein in the West for a long time. And consider alternatives to sugary treats and processed foods, such as fruit and dried fruits, which still contain natural sugars but come bound to fibre.

Enjoy going for walks and spending a little time moving around outside when possible. Exposure to other environments comes with exposure to other microbial ecosystems, which can form a part of the biomes on your skin, mouth, nose, and so on. While there may be a focus on the gut, all microbiomes are important.

And finally, look after your mental health by avoiding unnecessary stress and learning effective stress management techniques for unpleasant situations that can’t be avoided. Perhaps it goes without saying, but don’t create stressful situations either. A lot of stress can be avoided when we realise how much of it is created by our own unawareness of actions and thoughts. The impact of stress on your body and those living in it is catastrophic.

Closing Words

I hope this newsletter has been helpful for you. More so than ever before, I find myself being asked time and time again about gut health and fermentation, so I wanted to clear it up in one (hopefully) enjoyable read. I also see an appalling amount of misleading information, false promises, and in some cases dangerous claims being made, so I wanted to clear things up.

When and if there are any studies with a reliable degree of evidential substance published on the impacts of fermented foods as a living food on gut microbiome ecosystems, I will be sure to share more. But until then, without naming names or going after significant individuals, please do not fall for claims of certainty, especially when they’re trying to sell you something.

If you’re interested in further reading, you can use Pubmed on the National Institute of Health website to look up articles, but always check for conflict of interests and caveats.

I wish you all the very best and shall return to more of the usual format for next week. Have a wonderful week, and I’ll see you soon.

Sam

Thank you for sharing this hugely common sense approach to healthy eating - and just as importantly a healthy lifestyle. Correct me if I'm wrong but the essence seems to me be: eat lots of (ideally diverse and organic) plants and be happy.

Thanks for sharing so much of your research. I’m trying to repair my gut after a long course of antibiotics and, living with a sceptical scientist, have often wondered what the research actually shows. Like you I am careful of both modern research and ancient wisdom and try to listen to my body to decide what is helping. Luckily my sceptical scientist makes amazing sauerkraut because we love the flavour

I’m working hard to develop my forest gardening at home to provide me with diverse organic fruit, vegetables and herbs as I absolutely believe they are the key to good health. Including the activity of gardening and the mental health benefits of being outdoors in beautiful surroundings