A One Thousand Year Old Rose Recipe

An odyssey through scent, story, and the soft revolution of a flower

In language, longing, and power, between perfume and thorn, the rose has managed to root itself in far more than our gardens. It’s easy to forget, with a supermarket bouquet in hand, that this flower was once a sacred offering, a battlefield emblem, a flavour distilled from empire. A rose is not just a rose. It is inheritance.

My personal relationship with roses began long before I was born. In the northeast of England, when my grandad was a young boy, his father was the first person in our family to take steps towards owning his own home, securing a mortgage on a small property, where he planted a single rose bush in the front garden before his untimely death, at a younger age than I am now. His widow, my great grandmother, continued to pay ‘rent’ at the post office, not realising she was slowly buying the house one payment at a time.

When he moved out decades later, my grandad took a cutting from the rose that still stood in the front garden, and has subsequently grown it in the garden of every house he’s lived in since. It isn’t a particularly remarkable rose, nor does it have much culinary value, but it now grows in my brother’s garden too, along with other roses he collects. And now that I have my own garden at the farm, I too will take a cutting and plant one somewhere, in a secret location, where its meaning outside of our family can remain in blissful obscurity.

But how did we end up at a point where roses appear in gardens all over the world? We’ve trained our eyes to read roses in red: romance, danger, and apology. To follow the rose is to follow trade routes and religious mysticism, botany and rebellion, art and apothecary. Its scent alone, impossible to describe (yet here I am, writing a whole article about it), harder still to replicate, has driven entire industries and centuries of obsession. It is both the most familiar flower and one of the most misunderstood.

In this issue:

The rose’s mythic and botanical roots

Empress Joséphine and the politics of petals

Roses in Mughal hospitality and global cuisine

Perfume science and scent memory

Artistic symbolism from Dante to O’Keeffe

A monastic rose cordial recipe

Rose’s role in secrecy, grief, protest, and gardens

The five profiles of roses

Roots in Myth and Wildness

Before it was bred for theatre, the rose was a quiet, scrappy thing. Wild roses (Rosa gallica, Rosa canina, Rosa damascena) once crept across the hillsides of Central Asia and the Middle East, threading themselves into the margins of human settlement. They weren’t grown for beauty at first. They were simply noticed and collected. Their hips boiled into syrups. Their petals rubbed between fingers, where their fragrance could be remembered.

The rose is ancient. Fossils of Rosa species date back 35 million years, when whales still had ankles and forests grew closer to the poles. It was a warm, shifting world, and flowering plants like Rosa were just beginning to test the edges of what was possible. By the time the Persians began cultivating roses in earnest, the flower had already taken root in both soil and story. Myths flourished.

Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love, ran barefoot through a forest in search of her wounded lover, Adonis. In her desperation, she caught her foot on the thorn of a white rosebush. Her blood stained the petals red, making it the first of the red roses, born of love and injury entwined. In another telling, the wind god Zephyrus guided Chloris, goddess of flowers, to the lifeless body of a woodland nymph. Moved by pity, Chloris transformed her with the help of the gods: Aphrodite gave beauty, Dionysus poured nectar, and Apollo blessed the flower with sunlight. The nymph became the first rose, a mosaic of divine intention, and a collaboration of nature’s anthropomorphised gifts.

Damask roses, with their velvety scent and silken petals, likely emerged from a blend of Asian and Mediterranean ancestors. This tangled lineage gave rise to attar of rose, a distilled essence that became both a luxury and a legacy. Like wine or cheese, each region developed its own expression of the flower’s inner life.

From the sacred to the sensual, the rose soon entered religious consciousness. In Greece, it marked divine beauty. In Persia, it became a Sufi symbol of the soul’s unfolding. Mystics wrote of petals opening in rhythm with the heart, and in Christian tradition, it found its way into Marian iconography. The rosary. The rose window. A bloom for prayer.

Petals and Power

The rose also went to war. In England, it became the emblem of dynastic conflict: red for Lancaster, white for York. Known as the War of The Roses, the very same that influenced George R R Martin’s Game of Thrones series, in its resolution, it saw the red rose laid over the white, forming the Tudor rose, a stitched symbol of supposed peace.

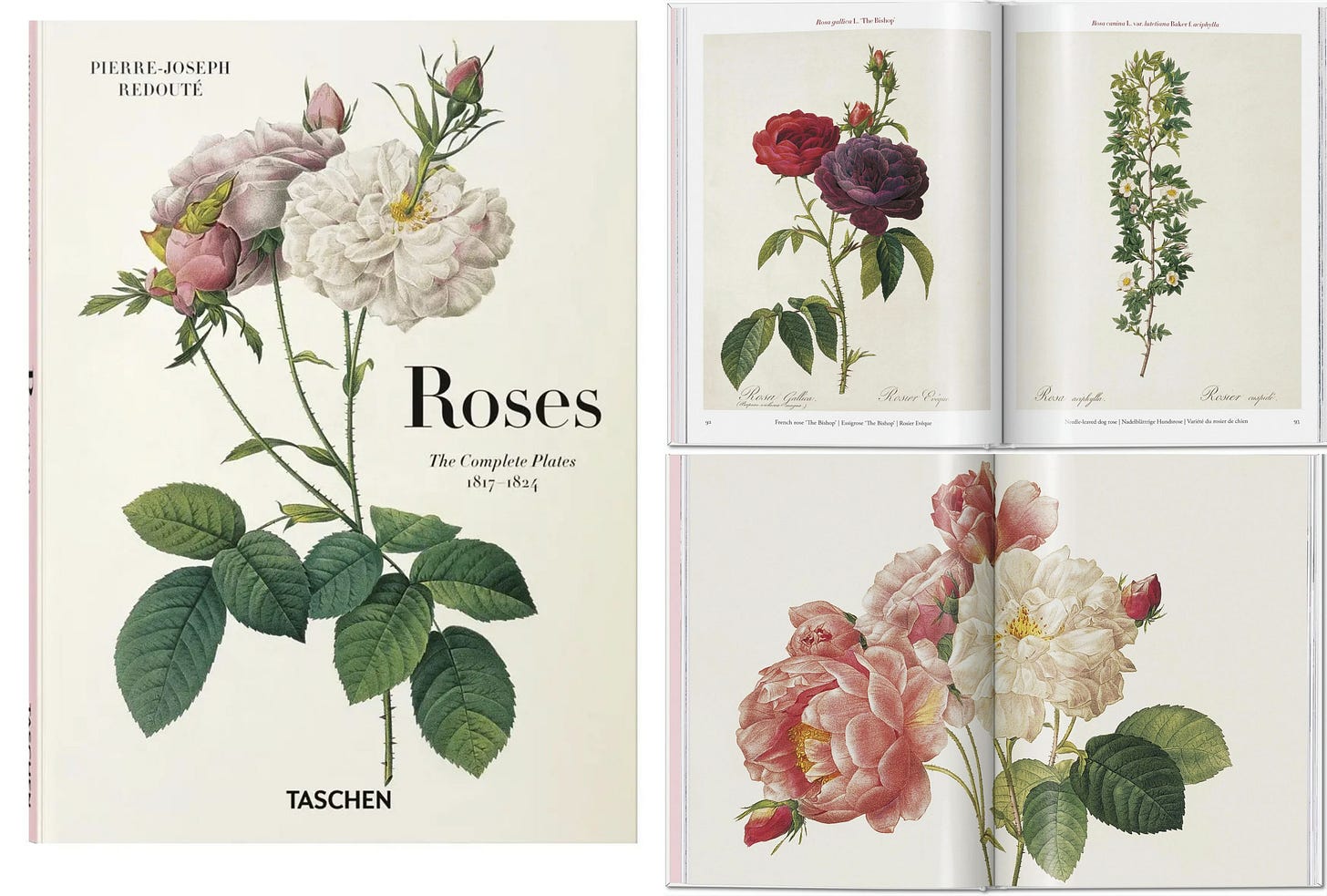

In France, Empress Joséphine built a garden of over 250 rose varieties at Malmaison, her private estate just outside Paris. It was her sanctuary, her stage, and ultimately her legacy. After her divorce from Napoleon, she poured her energy into cultivating beauty, gathering roses from across Europe and beyond. She employed painters like Pierre-Joseph Redouté to document the blooms in exquisite botanical detail, a visual archive that still stuns with its precision and tenderness. Her passion was not just ornamental. It was ambitious, political, deeply personal. Through her patronage, the rose ceased to be just a symbol and became a science, leading to a great boom in hybridisation. Naming conventions evolved, roses became status, story, and currency. Her garden laid the groundwork for modern rose breeding, a legacy written in fragrance, yes, but also in taxonomy, image, and desire.

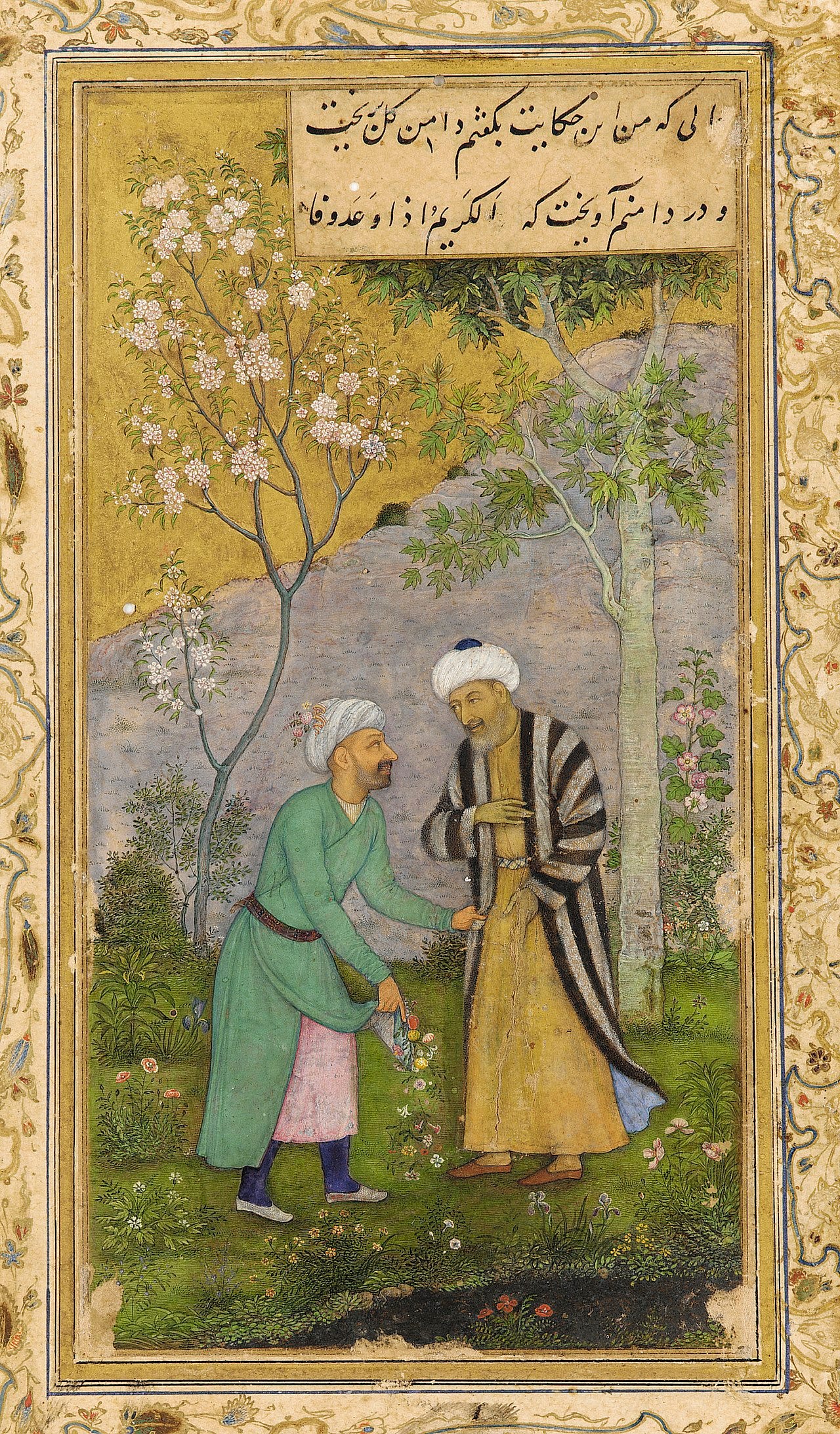

In Mughal and Persian courts, the rose was grown less for conquest than for awe. Garden design centred on scent and symmetry, not merely for decoration but for evocation. These were spaces meant to transport: the quadrants of the chahar bagh echoing paradise, water channels murmuring across tiled paths, rosebushes flanking every walkway. Scent marked every threshold. At banquets, rosewater was poured over guests' hands from silver vessels, a gesture of welcome and purification. Bowls of rice steamed with cardamom and saffron were infused with the same floral notes, layering fragrance into the grain. Sherbet, a chilled, sweet drink of rosewater and citrus, was served in crystal cut cups to soothe guests on hot days. Whilst to us it might seem opulent, it wasn’t opulence for opulence's sake. It was ritualised hospitality, where fragrance became a language of care and refinement.

Even in food, the rose refused to remain quiet. In Persia, it perfumed rice and saffron sweets. In Yazd, traditional pastries like noon-e berenji and qottab still carry the aroma of rose, passed down from kitchens that haven’t changed much in a hundred years. Perhaps most globally famous, in the Ottoman Empire, it gave Turkish delight its perfume; delicate, chewy, and dusted with icing sugar, where it lingers on the tongue and etches itself into memory. In England, rose once flavoured jams, custards, and meads. The old recipes remain in the corners of well-loved cookbooks and are seeing quiet revival in cottage kitchens (like my own). A syrup of petals, sugar, and lemon still recalls summer with a spoonful, especially when poured over yoghurt or folded into whipped cream for a midsummer pudding (read more below).

Medicinally, roses cooled fevers, eased grief, steadied the heart. They were thought to balance the humours, calm the nerves, and restore emotional clarity, unless of course, you suffer from hay fever like I do. Monks in medieval monastic gardens gathered rose petals not just for their scent, but for their ability to soothe the soul. They infused them into syrups and cordials, often alongside lemon balm, hawthorn, or honey. These were taken in small sips, not as an immediate cure, but for steady restoration. In the famous 14th-century herbal manuscript Tacuinum Sanitatis, rose preparations were recommended for melancholy and for the "heat of the blood."

One such cordial, found in variations in monastic and folk texts, can be made as follows:

Monastic Rose Cordial

Inspired by Hildegard of Bingen's writings and 17th-century herbal formulas

50g fresh, unsprayed rose petals (or 15g dried damask rose petals)

250ml local honey

500ml water

Zest of 1 organic lemon

Juice of 1/2 lemon

Optional: a sprig of lemon balm or fresh thyme

Gently rinse petals if fresh, and place in a pan with the water, lemon zest, and optional herbs.

Simmer gently for 15–20 minutes. Do not boil.

Strain through muslin, then add the honey and lemon juice while the infusion is still warm.

Bottle in a sterilised jar and keep refrigerated. It will last up to a month or two.

An additional tip, if you use preserving sugar instead of honey, the petals take on the texture of a chewy, gummy sweet which is pleasant to snack on or fold into other desserts.

Take a tablespoon stirred into warm water or tea, as the instructions state, during times of sadness.

Physicians prescribed rose vinegar to soothe inflammation and rose syrup to treat coughs or digestive imbalance. In traditional Chinese medicine, rosebuds are still steeped in hot water as a gentle tea to move stagnant qi and lighten emotional heaviness. Their efficacy was subtle and persistent.

Perfume & Memory

We chase the rose in perfume, but its scent defies capture. Over 400 volatile molecules compose its fragrance, each one reacting to temperature, light, and time like a living chord. A rose smells one way at dawn, another in full sun, another still in the hand of someone you love. Its scent is chemistry shaped by moment, which is why walking through a rose garden on a cool morning can feel different than brushing past the same bloom on a warm evening.

Most commercial perfumes replicate this scent synthetically. The real thing, true rose absolute, drawn from damask petals at sunrise, is expensive, vanishingly rare, and heartbreakingly hard to scale. It takes over a tonne of petals to make a single litre of oil. Even then, the perfume is fleeting. It sinks into skin and memory, then dissolves.

And yet, that impermanence is the very thing we find irresistible. It’s why we lift the wrist, close our eyes, inhale again. We know it won't last. That's the magic. Like catching someone’s laugh in a room and knowing you’ll remember the shape of it far longer than the sound.

The Rose Reimagined

In art and literature, the rose recurs with obsessive regularity. Dante imagines heaven as an unfolding rose, a great celestial bloom in which the souls of the blessed are arranged petal by petal. It is a structure of eternity made visible. Sappho, writing in fragments across time, invokes the rose to speak of longing, fragility, the softness of desire. The rose becomes a shorthand for feeling too large to name.

Perhaps most obviously, Georgia O’Keeffe turned the rose into near-abstraction. Her enormous, intimate oil paintings zoom in until the flower becomes landscape, a spiral of flesh, space, and suggestion. Critics, of course, couldn’t leave it alone. Observing the natural world is rarely enough, so they always have to find a way to make it smutty. Her roses have long been interpreted as feminine, erotic, and anatomical. But O’Keeffe herself said she simply wanted people to look. To truly see what a flower is when you give it your full attention.

William Blake, in contrast, saw the rose as already corrupted. In "The Sick Rose," he describes an invisible worm eating away at the heart of beauty. It is a poem of decay, secrecy, perhaps even shame. A flower undone from the inside. And then there is Shakespeare, how could we ignore him? In Juliet’s line, "A rose by any other name would smell as sweet," the flower becomes a tool of argument, a plea to strip away politics, to let love stand unlabelled. The rose isn’t questioned, but relied upon. Its scent, like love, is assumed to be constant, no matter how we name it.

Floriography, the Secret Language of Roses

In Victorian England, a time when propriety kept emotions corseted, floriography, the language of flowers, offered a way to speak without speaking. Red roses burned with passion. Yellow suggested betrayal. White meant purity, or the ache of grief. The colour alone could compose a letter. Entire messages were arranged into bouquets, handed off at doors or sent through intermediaries, every bloom charged with unsaid meaning. A rose could apologise, or promise, or end something.

The phrase “sub rosa”, under the rose, has older roots still. In Roman dining rooms, roses were carved into ceilings to signal confidentiality. What was spoken beneath the rose was never to be repeated. A symbol of discretion, still invoked today.

We still give roses to say the things we can’t quite phrase. We hand them to lovers, to the bereaved, to friends we’re trying to make amends with. They appear in the places where language fails: at the foot of a hospital bed, laid across a coffin, held tight in trembling hands during weddings. The same bloom that opens courtship often closes a chapter too. Pressed into the pages of a journal. Left on a doormat with no note. Kept long after they’ve dried out and begun to drop their petals. Roses speak into silence. They are a form of correspondence that needs no reply.

In Kitchens & Gardens

To preserve a rose is to attempt defiance. We try, again and again, to pin it in time. We dry the petals between heavy books, as if memory can be flattened and stored. We candy them, spin them into syrups, fold them into honey butter. We stir them into sugar ferments like cheong, or infuse them into vinegar for vinaigrettes that carry the hum of June into December. Even in the kitchen, the rose resists being forgotten. A spoonful of rose syrup into plain yoghurt, or a slice of almond cake perfumed with petal sugar. A floral afterlife that asks us to remember where we were when we picked them, and for whom.

In the garden, the rose earns its keep. Its prickles dissuade nibblers. Its hips feed the birds. Its deep roots hold the soil during heavy rain. It's why you'll often find garlic or lavender planted nearby, as gardeners favour companions that confuse pests, protect roots, and bring their own fragrances to the mix. Wild species roses knit themselves into hedgerows, forming a living barrier that shelters wrens and hedgehogs, shaping the garden’s skeleton. The ecosystem sees the rose for what it is: shelter, food source, boundary, medicine. And in autumn, when the petals fall, the rose bears fruit. Rose hips swell like tiny lanterns, scarlet, orange, plum. During the Second World War, British children were paid by the ounce to gather them. They were boiled into syrup, bottled and rationed, rich in vitamin C when citrus was scarce. Even now, they promise sustenance: brewed into tea, fermented into vinegar, simmered into jam. They mark the passage from bloom to nourishment. But that is a story better saved for the first frost.

The Five Fragrance Profiles of the Rose

A taxonomy of scent, mood, and memory

The scent of a rose isn’t one thing, it’s a spectrum. Not all roses smell the same, and thank goodness for that. Some bloom with a lemony brightness; others deepen toward honey, musk, or even clove. Growers, perfumers, and botanists have long categorised rose fragrances into five broad profiles, which I first learned about thanks to David Austen Roses. These aren’t rigid categories so much as recurring notes.

Understanding them helps you choose roses for your garden, your kitchen, or even your skin. But it also offers something deeper: a way to read a rose like a text, to listen more closely to what it’s saying.

1. Old Rose (Damask)

Scent: Rich, deep, and classic—the archetype

Mood: Romantic, nostalgic, warm

Notes: Warm spice, fruit preserves, powder

This is the fragrance most people think of when they think of a rose. Heavy, voluptuous, and velvety, it’s the scent of Rosa damascena, a rose cultivated for centuries in Persian, Bulgarian, and Turkish fields. Its scent is complex, honeyed, and often carries faint notes of ripe plums or mulled spice. If you’ve ever opened a jar of high-quality rose petal jam or sipped real rose tea, this is what you’re remembering.

2. Tea

Scent: Light, dry, and elegant

Mood: Reflective, delicate, clean

Notes: Dried hay and brewed tea leaves

Named not for the beverage but for the scent of the leaves themselves, tea-scented roses have a dry, ethereal aroma, often compared to fresh Darjeeling or oolong. Cultivars descended from Chinese species roses often carry this profile. There’s a gentleness here that feels unforced and meditative, like linen sheets or afternoon light on a windowsill. A tea rose doesn’t announce itself. It waits for you to notice.

3. Fruity

Scent: Bright, juicy, sunlit

Mood: Playful, summery, cheerful

Notes: Apple, raspberry, apricot, citrus peel

This category smells like an orchard in bloom. Fruity roses often carry hints of pear, green apple, citrus zest, or soft stone fruit. In some varieties, like Rosa ‘Jude the Obscure’ or Lady Emma Hamilton, the scent can verge on marmalade or muscat grape. This profile leans toward joy, evoking gardens in midsummer and the tactile pleasure of biting into something perfectly ripe. Sometimes, just sometimes, this one can smell a bit like soap in a grandmother’s downstairs bathroom.

4. Myrrh

Scent: Aniseed, resin, and bitter almond

Mood: Wistful, unusual, antique

Notes: Licorice, herbs, church incense

An acquired taste, but worth acquiring. Myrrh-scented roses are often described as ecclesiastical, they smell like altar smoke and history. This profile originated in some David Austin English roses and can seem otherworldly, even unsettling at first. But let it linger. The fragrance unfolds slowly, like a candlelit room warming over time. It smells of stories passed down, of something sacred that doesn’t quite want to be named.

5. Musk

Scent: Light, airy, and clean - but persistent

Mood: Enveloping, tender, elusive

Notes: Skin, beeswax, warm milk, pollen

Unlike synthetic musks in perfume, the musk in roses is floral and feathery. Musk roses (Rosa moschata) exude their scent in waves, especially in the evening, and often smell more like the space around the flower than the flower itself. It’s intimate. Subtle. The kind of scent you notice more on your clothes than on the bloom.

Why It Matters

The scent of a rose is chemistry and character. When you learn to distinguish these profiles, you’re really learning to pay closer attention. To notice how one rose might lean toward lemon and clove, while another tilts into honey and incense.

Whether you’re growing roses or stirring them into a syrup, it helps to know what story you’re working with.

Suggested Listening:

This week my song of choice is Sunday by Annahstasia, a song as tender and resolute as a rose, perfectly suited to reading about lineage, memory, and love. The song’s intimate, soulful tone, with its gentle, warming brass are present and enduring. Both the song and the rose are symbols of love in a sometimes mournful manner.

I would like to thank you for joining me on this journey into all things rose. If you’d like to see how I made rosehip cheong, jelly, vinegar, and lacto fermentation last year, you can find the full recipe here. It should keep you plenty busy until the next newsletter.

All the very best,

Sam

When I went to Turkey I was fortunate to join a tour to rose fields for dawn picking with village women. Then on to the distillery. The rose petals are stored in a bunker to air before being put in the still. We were allowed to sit in the shed of roses. You can imagine the scent! We were all euphoric, showering ourselves with so many rose petals. Quite the experience to remember.

A wonderful morning read Sam and definitely a recipe to try! We’ve yet to find wild roses here but will definitely plant some in time. We’ve also just bought a David Austin Pauls Himalayan Musk after being blown away by the ‘rose alleyway’ at Dan Yr Onnen.

The white rose is still the emblem of us Yorkshire tykes too!